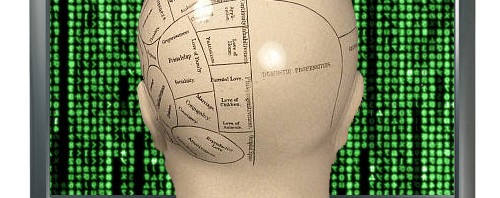

We watch films with our eyes and ears, but we experience films with our minds and bodies. Films do things to us, but we also do things with them. A film pulls a surprise; we jump. It sets up scenes; we follow them. It plants hints; we remember them. It prompts us to feel emotions; we feel them. If we want to know more—the how, the secrets of the craft—it would seem logical to ask the filmmakers. What enables them to get us to respond so precisely?

Unfortunately for us, they usually can’t tell us. Throughout history, filmmakers have worked with seat-of-the-pants psychology. By trial and error they have learned how to shape our minds and feelings, but usually they aren’t interested in explaining why they succeed. They leave that task to film scholars, psychologists, and others.

In an online essay on my blog, I survey of some major ways in which people thinking about cinema have floated psychological explanations for filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes filmmakers reflected on their own craft; more often the task of employing psychology to illuminate the viewer’s experience fell to journalists, critics, and academics. But most of them did not conduct careful historical or empirical research. This doesn’t make their ideas worthless, but it should incline us to see them as working informally. Sometimes they connect ideas about films’ effects on viewer to wider theories of mind; sometimes they don’t. When Film Studies entered universities in the 1960s, writers became more conscious of how specific schools of psychological research accorded with the filmic phenomena they wanted to study. Explicit or implicit, vague or precise, models of mind were recruited to explain the power of cinema.

I refer you to my blog, to read the essay in its entirety, at this link. I would appreciate continuing this conversation with my SCSMI colleagues, so I invite you to comment here.

Thanks to Dr. Bordwell for this excellent essay that extends the historical roots examined by Andrew and Casetti into modern cognitive theory in film studies. I wish I had had this essay when I was working on my book Psychology at the Movies (Wiley-Blackwell). In that book I take an interdisciplinary approach to psychology and summarize many areas of scholarship for an introductory audience.

I was aware as I was juxtaposing psychoanalytic interpretations, content analyses of psychologists in film, experiments on the effects of film, etc., that these approaches had little contact with each other outside of my book. Interdisciplinarity (particularly between the humanities and the sciences) is hard to pull off these days. It is for that reason that I am so impressed with the work of Bordwell and the many others he summarizes in his essay. The cognitive turn in film studies represents a genuine interdisciplinary success story.

As a clinical psychologist however I am curious about the potential for this movement to shed light on what I call “movies as equipment for living” (stealing from Kenneth Burke). Cognitive science sometimes stops short of psychological issues like identity construction and personal growth. This is understandable as it gets into the very murky area of meaning making (the same murky area Bordwell has understandably criticized when it comes to film studies). Still, I think movies are ultimately interesting to people because particular movies really matter to us as individuals. As I mention in another thread, I am therefore extremely interested in Carroll’s key note address at the SCSMI conference where he looks at the role of movie viewing and the development of virtuous behavior. I am hopeful that the interdisciplinary vision that has developed in film studies over the past 20 years can be fruitfully applied to humanities end of the psychological spectrum (e.g., self, experience, symbols, etc).

July, 2nd 2012, Parma, Italy

I totally agree with David Bordwell’s post and I’ve enjoyed the article on his blog very much. These few lines just to say that at the University of Parma Vittorio Gallese (one of the discoverers of mirror neurons) and I are working on the relationship between embodied simulation (ES) and the movies. ES has been proposed to constitute a basic functional mechanism of humans’ brain, by means of which actions, emotions and sensations of others are mapped onto the observer’s own sensory-motor and viscero-motor neural representation. We posit that ES characterize the perceived object in terms of motor acts it may afford, even in absence of any effective movement. In other words, ES can help us in understanding how we inhabit a space and how we move through it. The idea is that movies are very useful models of virtual space we inhabit, and in which we move and act, sharing attitudes and behaviors not only with characters but also with the camera and film style. The movie becomes part of our peri-personal space, a multisensory and body-centered space, which is motor in nature (Lumière Bros.’ goal was placing the world within one’s reach, that is within our peri-personal space). Our motor and pre-motor attitudes are crucial in understanding how we experience a movie. As Merleau-Ponty put it, “On perçoit donc le mouvement, son sens, son allure caractéristique, par [les] possibilités motrices du corps propre.” (M. Merleau-Ponty, Le monde sensible et le monde de l’expression, Genève : Metis, 2011, p. 119).

Since the movies are usually goal-oriented and action-packed, this kind of research could be useful for the comprehension of our film experience and our emotions. To us, ES could represent an interesting way to approach the history of film style on a motor and enteroceptive basis, considering it both from the filmmaker’s and from the viewer’s side. At the moment we are working on camera movements, and on the different gazes the camera eye can convey (POV shots, over-the shoulder shots and false POV shots), studying the different levels of “resonance†in the viewer.

Obviously we hope that this “subpersonal†research will offer good insights to widen the cognitive approach to film studies. I’ll be happy to keep SCSMI members updated on our work.

Best,

Michele Guerra